WASHINGTON (CN) — A copyright case involving famous photographs of the late musician Prince had the justices pondering how to protect art without stifling its creation during Wednesday morning oral arguments.

“The purpose of all copyright law is to foster creativity,” Justice Elena Kagan said.

With multiple bouts of laughter and jokes from the normally solemn court, the uncharacteristically raucous session had the justices revealing some of their creative preferences.

“Let’s say that I’m a Prince fan, which I was in the ‘80s,” Justice Clarence Thomas said.

“No longer?” Justice Elena Kagan inquired. To which Thomas clarified, “only on Thursday night.”

Justice Amy Coney Barrett appeared partial to the “Lord of the Rings,” asking if a ruling in this case could impact book-to-film adaptations. The Trump appointee appeared shocked when an attorney suggested the book and movies were one and the same.

“It is not every day that Supreme Court oral arguments include references to ‘Lord of the Rings’ (both the books and the movies!), the Syracuse University athletic program, ‘Mork and Mindy,’ ‘All in the Family,’ Norman Lear (inaccurately characterized as having passed away, when he just celebrated his 100th birthday), the Mona Lisa (in a red dress, yet), photos of Abraham Lincoln and biographies of George Washington, but today’s oral argument in the case of Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith included all of that and plenty more,” said Bruce Ewing, head of Dorsey & Whitney’s trial department and co-chair of the firm’s Intellectual Property Litigation Practice Group, in a statement.

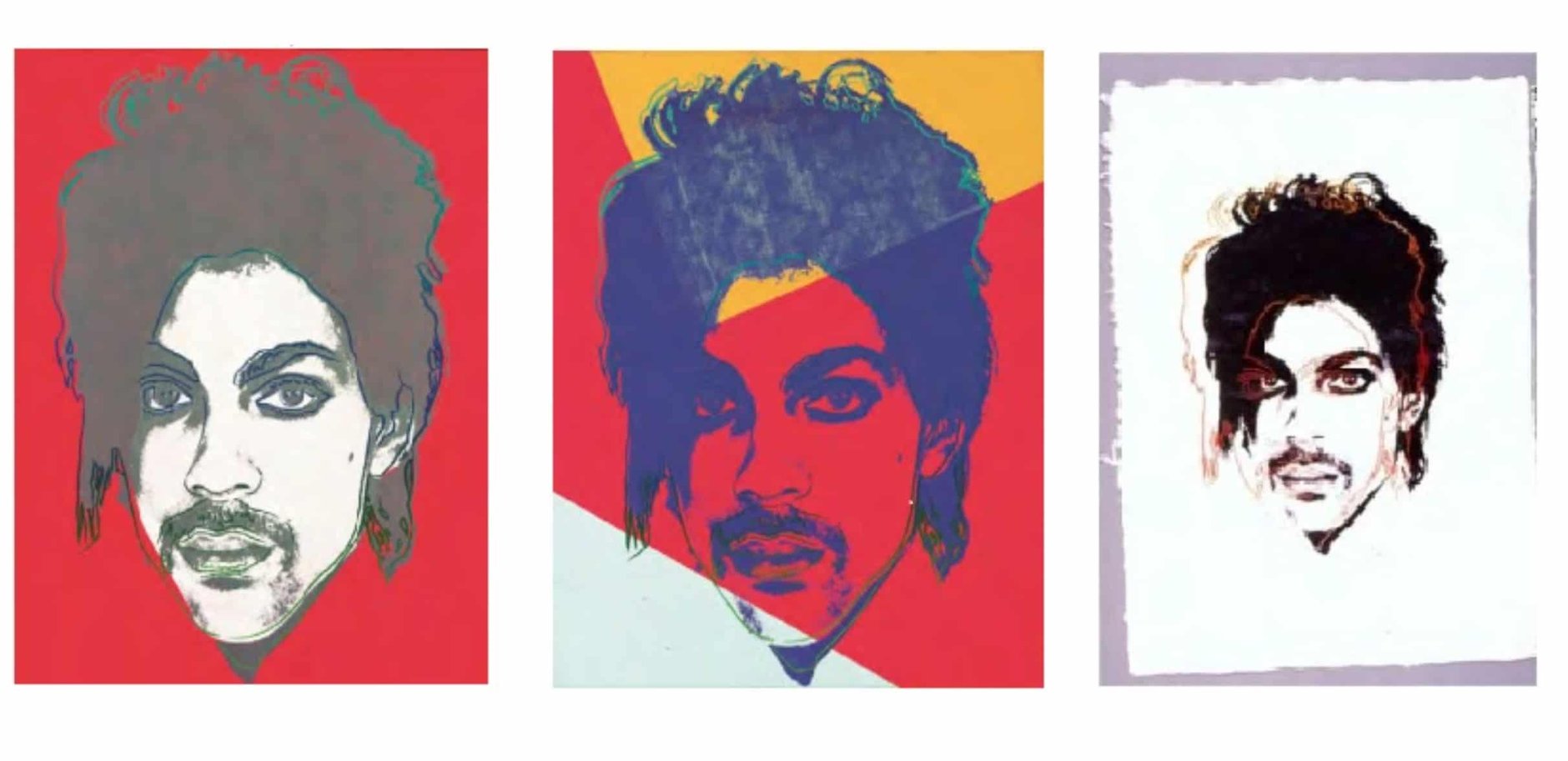

The case before the court stems from an Andy Warhol work. For a 1984 article titled “Purple Fame,” Vanity Fair commissioned Warhol to create art. The magazine supplied images from celebrity photographer Lynn Goldsmith as a reference. Instead of just creating one piece for the article, Warhol produced 12 silkscreen paintings that would come to be known as the Prince Series. Goldsmith’s original photos were altered to add layers of colors, and outlined to accentuate Prince’s features. Warhol also resized and cropped the images, changing the tones, lighting and detail.

The Prince Series resurfaced in Vanity Fair in 2016 after Prince’s death when the magazine reposted the “Purple Fame” article online. A commemorative magazine also used the prints. This would lead to a legal battle stretching to the high court.

Goldsmith claims the Prince Series infringed on her copyright. The Warhol Foundation then filed a declaratory judgment that the Prince Series is protected by fair use. Goldsmith filed a counterclaim.

Fair use is an exception to the Copyright Act that allows the exclusive rights of creators to be breached without infringement on an artist's copyright. There are four factors that are considered but the court was principally focused on only one of those factors in arguments on Wednesday: the purpose and character of the art’s use.

The Warhol Foundation argues that a follow-on work is transformative — and therefore qualifies under fair use — if it provides a new meaning or message. While a federal judge agreed with the foundation, the Second Circuit did not. Now the justices are left to decide if conveying a new meaning or message classifies a follow-on work as transformative.

By conveying a fundamentally different meaning from the original work, the foundation claims it has not violated Goldsmith’s copyright. The foundation argued that the justices’ didn’t need to decide if Warhol’s work was different than Goldsmith’s, just if that should be taken into consideration.

“There's no real dispute in this case that the meaning or message of the two works were different,” said Roman Martinez, an attorney for the foundation with Latham & Watkins. “The only real question in this case is whether that difference matters.”

If the court were to decide that the meaning or message of a follow-on work did not matter, the foundation said there could be dire consequences for artists.

“This case is not just about the use, it’s about the creation,” Martinez said. “The reason that [Goldsmith] wants to change the subject and make it only about creation … is because she realizes that if this case is about the creation of the works, then it would have dramatic spillover consequences — not just for the Prince Series but for all sorts of works of modern art that incorporates preexisting images and using preexisting images as raw material in generating completely new creative expression by follow-on artists.”

Goldsmith argues, however, that if the court were to accept Warhol’s arguments, it would wreak havoc on creator’s original works.

“If petitioner’s test prevails, copyrights will be at the mercy of copycats,” Williams & Connolly attorney Lisa Blatt, representing Goldsmith, said. “Anyone could turn Darth Vader into a hero or spring off ‘All in the Family’ into ‘The Jeffersons’ without paying the creators a dime.”

The justices spent most of the argument session drilling down on how the meaning or message of a work relates to its use.

“There may be a different meaning or message, but if both of those depictions are going in a magazine for commercial nature, the purpose, the reason why you’ve used it, is the same,” Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson said.

Justice Neil Gorsuch distinguished between the Prince Series, which he said had a commercial purpose, and Warhol’s iconic images of Campbell’s soup cans.

“The purpose of the use for Any Warhol was not to sell tomato soup in a supermarket,” the Trump appointee said.

Justice Samuel Alito appeared concerned over who would assume the task of interpreting the meaning of art in similar cases.

“How is a court to determine the purpose of the message or meaning of works of art like a photographer or a painting,” the Bush appointee said.

He continued: “You make it sound simple, but maybe it’s not so simple, at least in some cases, to determine what is the meaning or the message of a work of art. There can be a lot of dispute about what the meaning or message is.”

The justices offered no clear indication on how they might rule in the case. Some of the justices seemed inclined to send the case back down to the lower courts.

“The Supreme Court argument did not clarify whether the balance is likely to tip in favor of one right or the other, or how to demarcate the boundaries between a use that is infringing and a use that is fair,” Ewing said. “Equally unclear is whether the court will issue a limited ruling that does little more than address either the specific facts of this dispute or the interpretation of the first fair use factors or offer a broader balancing test capable of wider applicability in copyright cases that covers fair use as a whole. The decision, when it comes down, likely in 2023, will surely be an interesting and important read regardless of the outcome.”

Subscribe to Closing Arguments

Sign up for new weekly newsletter Closing Arguments to get the latest about ongoing trials, major litigation and hot cases and rulings in courthouses around the U.S. and the world.