Turkey’s president has enjoyed an unusually powerful sway over the Trump administration. A new investigation reveals the relationship was built by a circle featuring Trump’s favorite lobbyist as well as a key character in the Ukraine impeachment scandal, a Kremlin-linked oligarch and a shipping tycoon charged with terrorism.

It was the day before Donald Trump’s inauguration and, over lunch at Washington’s Watergate Hotel, a foreign government was trying to break into the new U.S. administration.

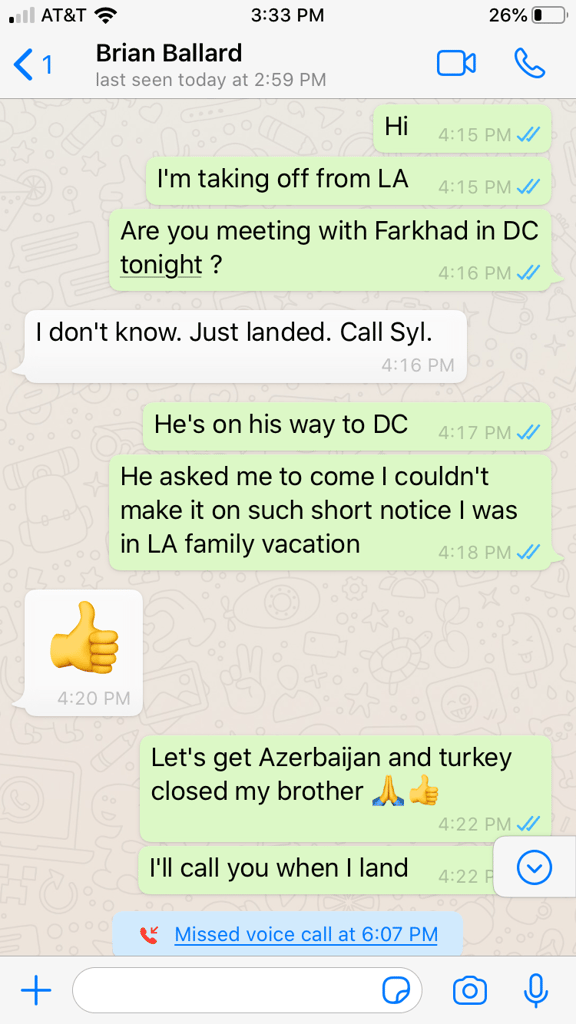

Meeting for the first time to talk business were Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu, Turkey’s foreign minister, and Brian Ballard, a powerful lobbyist then serving as vice chairman of Trump’s inaugural committee.

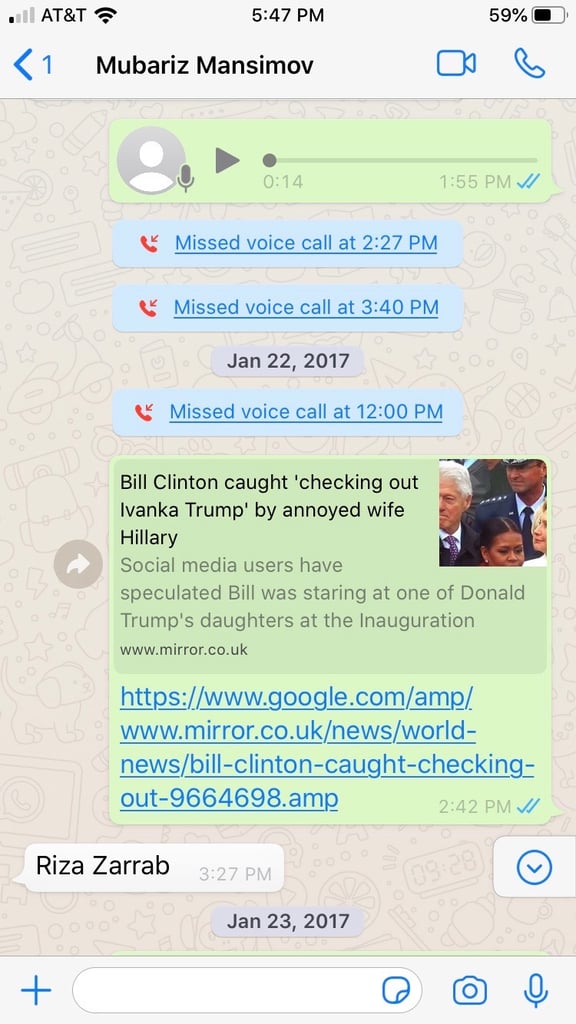

Also present were the two men who set up the meeting. One was Lev Parnas, a Florida businessman whose backchannel dealings in Ukraine would, nearly three years later, lead to Trump’s impeachment. The other was Mübariz Mansimov, a Turkish-Azerbaijani shipping magnate being tried in Turkey today on terrorism charges.

The January 19, 2017, meeting, which has never before been disclosed, was key to building a close relationship between the administrations of Trump and Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. It has perhaps been the most successful foreign lobbying effort of the Trump presidency — no mean feat for an administration mired from the beginning in foreign influence scandals.

On the agenda were what would become two multimillion-dollar contracts to lobby for Turkey and its Islamist leader, Erdoğan, in the U.S. For Parnas, one of the middlemen, it represented a potential payday. (The firm did not deny the meeting.)

“There was a lot of bodyguards, Turkish bodyguards,” Parnas recalled in a 90-minute interview. “It was in a little restaurant. We went in. [Çavuşoğlu] was sitting in the restaurant with a couple of other Turkish dignitaries.”

“Mübariz introduced Brian Ballard as ‘Trump’s No. 1 guy,’” Parnas said of the top Trump fundraiser from Florida, whom Politico dubbed “The Most Powerful Lobbyist in Trump’s Washington.”

The warm relationship that followed would see Trump administration officials, and the president himself, make decisions that baffled advisers who believed they put Erdoğan’s interests over America’s.

In a recent memoir, Trump’s former national security adviser, John Bolton, described a “bromance” between the two leaders.

But behind that bromance is a deeper story — one that involves Russia-linked oligarchs, alleged crooks and key players in the Ukraine scandal that got Trump impeached, an investigation by OCCRP, Courthouse News Service and NBC News has found.

Sitting down for 90 minutes for his first interview on this topic, Parnas also exclusively shared corroborating photographic, video and documentary evidence. Through independently gathered interviews, court records, flight records and other information, reporters discovered that Turkey built much of its relationship with the Trump administration via an international network of businessmen and oligarchs — most of whom are linked to the former Soviet republics, and nearly all of whom are now either in jail or facing serious criminal charges.

The lobbying contracts with Ballard were established with the help of both Parnas and the shipping tycoon Mansimov, as well as Farkhad Akhmedov, who is listed by the U.S. Treasury as a Russian oligarch closely tied to Russian President Vladimir Putin. Neither man replied to written questions.

The contracts eventually included a $125,000-per-month deal for Ballard’s firm to represent Halkbank, a Turkish state bank being prosecuted in the United States for fraud, money laundering and sanction offences, public records show. According to Bolton, Parnas, congressional investigators and multiple news reports, Trump has tried to quash the Halkbank case.